Nonprofit organization with charitable purpose

For other uses, see Charity (disambiguation).

Not to be confused with Charites.

American Cancer Society offices in Washington, D.C.

American Cancer Society offices in Washington, D.C.

A charitable organization[1] or charity is an organization whose primary objectives are philanthropy and social well-being (e.g. educational, religious or other activities serving the public interest or common good).

The legal definition of a charitable organization (and of charity) varies between countries and in some instances regions of the country. The regulation, the tax treatment, and the way in which charity law affects charitable organizations also vary. Charitable organizations may not use any of their funds to profit individual persons or entities.[2] However, some charitable organizations have come under scrutiny for spending a disproportionate amount of their income to pay the salaries of their leadership.

The second-hand shop of UFF (U-landshjälp från Folk till Folk i Finland), a non-profit and non-governmental humanitarian foundation,[3] in Jyväskylä, Finland

The second-hand shop of UFF (U-landshjälp från Folk till Folk i Finland), a non-profit and non-governmental humanitarian foundation,[3] in Jyväskylä, Finland

Financial figures (e.g. tax refund, revenue from fundraising, revenue from the sale of goods and services or revenue from investment) are indicators to assess the financial sustainability of a charity, especially to charity evaluators. This information can impact a charity's reputation with donors and societies, and thus the charity's financial gains.

Charitable organizations often depend partly on donations from businesses. Such donations to charitable organizations represent a major form of corporate philanthropy.[4]

To meet the exempt organizational test requirements, a charity has to be exclusively organized and operated,[1] and to receive and pass the exemption test, a charitable organization must follow the public interest and all exempt income should be for the public interest.[1] For example, in many countries of the Commonwealth, charitable organizations must demonstrate that they provide a public benefit.[5]

History

[edit]

|

|

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the English-speaking world and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this article, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new article, as appropriate. (September 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

Early systems

[edit]

Until the mid-18th century, charity was mainly distributed through religious structures (such as the English Poor Laws of 1601), almshouses, and bequests from the rich. Christianity, Judaism, and Islam incorporated significant charitable elements from their very beginnings,[6] and dÄÂna (alms-giving) has a long tradition in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. Charities provided education, health, housing, and even prisons. Almshouses were established throughout Europe in the Early Middle Ages to provide a place of residence for the poor, old, and distressed people; King Athelstan of England (reigned 924–939) founded the first recorded almshouse in York in the 10th century.[7]

Enlightenment charity

[edit]

The Foundling Hospital, whose building has been demolished

The Foundling Hospital, whose building has been demolished

During the Enlightenment era, charitable and philanthropic activity among voluntary associations and affluent benefactors became a widespread cultural practice. Societies, gentlemen's clubs, and mutual associations began to flourish in England, with the upper classes increasingly adopting a philanthropic attitude toward the disadvantaged. In England, this new social activism led to the establishment of charitable organizations, which proliferated from the middle of the 18th century.[8]

This emerging upper-class trend for benevolence resulted in the incorporation of the first charitable organizations. Appalled by the number of abandoned children living on the streets of London, Captain Thomas Coram set up the Foundling Hospital in 1741 to care for these unwanted orphans in Lamb's Conduit Fields, Bloomsbury. This institution, the world's first of its kind,[9] served as the precedent for incorporated associational charities in general.[10]

Painting by Antoine-Alexandre Morel (1765–1829) depicting charity during the Enlightenment era

Painting by Antoine-Alexandre Morel (1765–1829) depicting charity during the Enlightenment era

Another notable philanthropist of the Enlightenment era, Jonas Hanway, established The Marine Society in 1756 as the first seafarers' charity, aiming to aid the recruitment of men into the navy.[11] By 1763, the Society had enlisted over 10,000 men, and an Act of Parliament incorporated it in 1772. Hanway also played a key role in founding the Magdalen Hospital to rehabilitate prostitutes. These organizations were funded by subscriptions and operated as voluntary associations. They raised public awareness about their activities through the emerging popular press and generally enjoyed high social regard. Some charities received state recognition in the form of a royal charter.

Charities also began to take on campaigning roles, championing causes and lobbying the government for legislative changes. This included organized campaigns against the mistreatment of animals and children, as well as the successful campaign in the early 19th century to end the slave trade throughout the British Empire and its extensive sphere of influence.[12] (However, this process was quite lengthy, concluding when slavery in Saudi Arabia was abolished slavery in 1962.)

The Enlightenment era also witnessed a growing philosophical debate between those advocating for state intervention and those believing that private charities should provide welfare. The political economist, Reverend Thomas Malthus (1766–1834), criticized poor relief for paupers on economic and moral grounds and proposed leaving charity entirely to the private sector.[13] His views became highly influential and informed the Victorian laissez-faire attitude toward state intervention for the poor.

Growth during the 19th century

[edit]

During the 19th century, a profusion of charitable organizations emerged to alleviate the awful conditions of the working class in the slums. The Labourer's Friend Society, chaired by Lord Shaftesbury in the United Kingdom in 1830, aimed to improve working-class conditions. It promoted, for example, the allotment of land to laborers for "cottage husbandry", which later became the allotment movement. In 1844, it became the first Model Dwellings Company – one of a group of organizations that sought to improve the housing conditions of the working classes by building new homes for them, all the while receiving a competitive rate of return on any investment. This was one of the first housing associations, a philanthropic endeavor that flourished in the second half of the nineteenth century, brought about by the growth of the middle class. Later associations included the Peabody Trust (originating in 1862) and the Guinness Trust (founded in 1890). The principle of philanthropic intention with capitalist return was given the label "five percent philanthropy".[14]

Andrew Carnegie's philanthropy. Puck magazine cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, 1903.

Andrew Carnegie's philanthropy. Puck magazine cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, 1903.

There was strong growth in municipal charities. The Brougham Commission led to the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, which reorganized multiple local charities by incorporating them into single entities under supervision from the local government.

Charities at the time, including the Charity Organization Society (established in 1869), tended to discriminate between the "deserving poor", who would be provided with suitable relief, and the "underserving" or "improvident poor", who was regarded as the cause of their woes due to their idleness. Charities tended to oppose the provision of welfare by the state, due to the perceived demoralizing effect. Although minimal state involvement was the dominant philosophy of the period, there was still significant government involvement in the form of statutory regulation and even limited funding.[15]

Philanthropy became a very fashionable activity among the expanding middle classes in Britain and America. Octavia Hill (1838–1912) and John Ruskin (1819–1900) were important forces behind the development of social housing, and Andrew Carnegie (1835–1919) exemplified the large-scale philanthropy of the newly rich in industrialized America. In Gospel of Wealth (1889), Carnegie wrote about the responsibilities of great wealth and the importance of social justice. He established public libraries throughout English-speaking countries[16] and contributed large sums to schools and universities.[17] A little over ten years after his retirement, Carnegie had given away over 90% of his fortune.[18]

Towards the end of the 19th century, with the advent of the New Liberalism and the innovative work of Charles Booth in documenting working-class life in London, attitudes towards poverty began to change. This led to the first social liberal welfare reforms, including the provision of old age pensions[19] and free school-meals.[20]

Since 1901

[edit]

During the 20th century, charitable organizations such as Oxfam (established in 1947), Care International, and Amnesty International expanded greatly, becoming large, multinational non-governmental organizations with very large budgets.

Since the 21st century

[edit]

With the advent of the Internet, charitable organizations established a presence on online social media platforms and began initiatives such as cyber-based humanitarian crowdfunding, exemplified by platforms like GoFundMe.

By jurisdiction

[edit]

Australia

[edit]

The definition of charity in Australia is derived from English common law, originally from the Charitable Uses Act 1601, and then through several centuries of case law based upon it. In 2002, the federal government initiated an inquiry into the definition of a charity. The inquiry proposed a statutory definition of a charity, based on the principles developed through case law. This led to the Charities Bill 2003, which included limitations on the involvement of charities in political campaigning, an unwelcome departure from the case law as perceived by many charities. The government appointed a Board of Taxation inquiry to consult with charities on the bill. However, due to widespread criticism from charities, the government abandoned the bill.

Subsequently, the government introduced the Extension of Charitable Purpose Act 2004. This act did not attempt to codify the definition of a charitable purpose but rather aimed to clarify that certain purposes were charitable, resolving legal doubts surrounding their charitable status. Among these purposes were childcare, self-help groups, and closed/contemplative religious orders.[21]

To publicly raise funds, a charity in Australia must register in each Australian jurisdiction in which it intends to raise funds. For example, in Queensland, charities must register with the Queensland Office of Fair Trading.[22] Additionally, any charity fundraising online must obtain approval from every Australian jurisdiction that mandates such approval. Currently, these jurisdictions include New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria, Tasmania, Western Australia, and the Australian Capital Territory. Numerous Australian charities have appealed to federal, state, and territory governments to establish uniform legislation enabling charities registered in one state or territory to raise funds in all other Australian jurisdictions.

The Australian Charities and Not-For-Profits Commission (ACNC) commenced operations in December 2012. It regulates approximately 56,000 non-profit organizations with tax-exempt status, along with around 600,000 other NPOs in total, seeking to standardize state-based fund-raising laws.[23]

A Public Benevolent Institution (PBI) is a specific type of charity with its primary purpose being to alleviate suffering in the community, whether due to poverty, sickness, or disability. Examples of institutions that might qualify include hospices, providers of subsidized housing, and certain not-for-profit aged care services.[24][25]

Canada

[edit]

Main article: Charitable organization (Canada)

Charities in Canada need to be registered with the Charities Directorate[26] of the Canada Revenue Agency. According to the Canada Revenue Agency:[27]

A registered charity is an organization established and operated for charitable purposes. It must devote its resources to charitable activities. The charity must be a resident in Canada and cannot use its income to benefit its members. A charity also has to meet a public benefit test. To qualify under this test, an organization must show that:

- its activities and purposes provide a tangible benefit to the public.

- those eligible for benefits are either the public as a whole or a significant section of it. They should not be a restricted group or one where members share a private connection, such as social clubs or professional associations with specific memberships.

- the charity's activities must be legal and must not be contrary to public policy.

To register as a charity, the organization has to be either incorporated or governed by a legal document called a trust or a constitution. This document has to explain the organization's purposes and structure.

France

[edit]

Most French charities are registered under the statute of loi d'association de 1901, a type of legal entity for non-profit NGOs. This statute is extremely common in France for any type of group that wants to be institutionalized (sports clubs, book clubs, support groups...), as it is very easy to set up and requires very little documentation. However, for an organization under the statute of loi 1901 to be considered a charity, it has to file with the authorities to come under the label of "association d'utilité publique", which means "NGO acting for the public interest". This label gives the NGO some tax exemptions.[citation needed]

Hungary

[edit]

In Hungary, charitable organizations are referred to as "public-benefit organizations" (Hungarian: közhasznú szervezet). The term was introduced on 1 January 1997 through the Act on Public Benefit Organizations.[28]

India

[edit]

Under Indian law, legal entities such as charitable organizations, corporations, and managing bodies have been given the status of "legal persons" with legal rights, such as the right to sue and be sued, and the right to own and transfer property.[29] Indian charitable organizations with this status include Sir Ratan Tata Trust.

Ireland

[edit]

In Ireland, the Charities Act (2009) legislated the establishment of a "Charities Regulatory Authority", and the Charities Regulator was subsequently created via a ministerial order in 2014.[30][31] This was the first legal framework for charity registration in Ireland. The Charities Regulator maintains a database of organizations that have been granted charitable tax exemption—a list previously maintained by the Revenue Commissioners.[32] Such organizations would have a CHY number from the Revenue Commissioners, a CRO number from the Companies Registration Office, and a charity number from the Charities Regulator.

The Irish Nonprofits Database was created by Irish Nonprofits Knowledge Exchange (INKEx) to serve as a repository for regulatory and voluntarily disclosed information about Irish public benefit nonprofits.[citation needed]

Nigeria

[edit]

Charitable organizations in Nigeria are registerable under "Part C" of the Companies and Allied Matters Act, 2020. Under the law, the Corporate Affairs Commission, Nigeria, being the official Nigerian Corporate Registry, is empowered to maintain and regulate the formation, operation, and dissolution of charitable organizations in Nigeria.[33] Charitable organizations in Nigeria are exempted under §25(c) of the Companies Income Tax Act (CITA) Cap. C21 LFN 2004 (as amended), which exempts from income tax corporate organizations engaged wholly in ecclesiastical, charitable, or educational activities.[34] Similarly, §3 of the Value Added Tax Act (VATA) Cap. V1 LFN 2004 (as amended), and the 1st Schedule to the VATA on exempted Goods and Services goods zero-rates goods and services purchased by any ecclesiastical, charitable, or educational institutions in furtherance of their charitable mandates.

Poland

[edit]

A public benefit organization (Polish: organizacja pożytku publicznego, often abbreviated as OPP) is a term used in Polish law. It was introduced on 1 January 2004 by the statute on public good activity and volunteering. Charitable organizations of public good are allowed to receive 1.5% of income tax from individuals, making them "tax-deductible organizations". To receive such status, an organization has to be a non-governmental organization, with political parties and trade unions not qualifying. The organization must also be involved in specific activities related to the public good as described by the law, and it should demonstrate sufficient transparency in its activities, governance, and finances. Moreover, data has shown that this evidence is pertinent and sensible.

Polish charitable organizations with this status include ZwiÄ…zek Harcerstwa Polskiego, the Great Orchestra of Christmas Charity, KARTA Center, the Institute of Public Affairs, the Silesian Fantasy Club, the Polish Historical Society, and the Polish chapter of the Wikimedia Foundation.

Singapore

[edit]

The legal framework in Singapore is regulated by the Singapore Charities Act (Chapter 37).[35] Charities in Singapore must be registered with the Charities Directorate of the Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports.[36] One can also find specific organizations that are members of the National Council of Social Service (NCSS), which is operated by the Ministry of Social and Family Development.

Ukraine

[edit]

The legislation governing charitable activities and the process of obtaining charitable organization status is regulated by Ukraine's Civil Code and the Law of Ukraine on Charitable Activities and Charitable Organizations.

According to Ukrainian law, there are three forms of charitable organizations:

- A "charitable society" is a charitable organization created by at least two founders and operates based on the charter or statute.

- A "charitable institution" is a type of charitable trust that acts based on the constituent or founding act. This charitable organization's founding act defines the assets that one or several founders transfer to achieve the goals of charitable activity, along with any income from such assets. A constituent act of a charitable institution may be contained in a will or testament. The founder or founders of the charitable institution do not participate in the management of such a charitable organization.

- A "charitable fund" or "charitable foundation" is a charitable organization that operates based on the charter, has participants or members, and is managed by them. Participants or members are not obliged to transfer any assets to such an organization to achieve the goals of charitable activity. A charitable foundation can be created by one or several founders. The assets of a charitable fund can be formed by participants and/or other benefactors.[citation needed]

The Ministry of Justice of Ukraine is the main registration authority for charitable organization registration and constitution.[37] Individuals and legal entities, except for public authorities and local governments, can be the founders of charitable organizations. Charitable societies and charitable foundations may have, in addition to founders, other participants who have joined them as prescribed by the charters of such charitable associations or charitable foundations. Aliens (non-Ukrainian citizens and legal entities, corporations, or non-governmental organizations) can be the founders and members of philanthropic organizations in Ukraine.

All funds received by a charitable organization and used for charitable purposes are exempt from taxation, but obtaining non-profit status from the tax authority is necessary.

Legalization is required for international charitable funds to operate in Ukraine.[clarification needed]

United Kingdom

[edit]

Charity law in the UK varies among (i) England and Wales, (ii) Scotland and (iii) Northern Ireland, but the fundamental principles are the same. Most organizations that are charities are required to be registered with the appropriate regulator for their jurisdiction, but significant exceptions apply so that many organizations are bona fide charities but do not appear on a public register.[38] The registers are maintained by the Charity Commission for England and Wales and by the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator for Scotland. The Charity Commission for Northern Ireland maintains a register of charities that have completed formal registration (see below). Organizations applying must meet the specific legal requirements summarized below, have filing requirements with their regulator, and are subject to inspection or other forms of review. The oldest charity in the UK is The King's School, Canterbury, established in 597 AD.[39]

Charitable organizations, including charitable trusts, are eligible for a complex set of reliefs and exemptions from taxation in the UK. These include reliefs and exemptions in relation to income tax, capital gains tax, inheritance tax, stamp duty land tax, and value added tax. These tax exemptions have led to criticisms that private schools are able to use charitable status as a tax avoidance technique rather than offering a genuine charitable good.[40]

The Transparency of Lobbying, Non-party Campaigning and Trade Union Administration Act 2014 subjects charities to regulation by the Electoral Commission in the run-up to a general election.[41]

England and Wales

[edit]

Definition

[edit]

Section 1 of the Charities Act 2011 provides the definition in England and Wales:

- (1) For the purposes of the law of England and Wales, "charity" means an institution which—

- (a) is established for charitable purposes only, and

- (b) falls to be subject to the control of the High Court in the exercise of its jurisdiction with respect to charities.

The Charities Act 2011 provides the following list of charitable purposes:[42]

- the prevention or relief of poverty

- the advancement of education

- the advancement of religion

- the advancement of health or the saving of lives

- the advancement of citizenship or community development

- the advancement of the arts, culture, heritage or science

- the advancement of amateur sport

- the advancement of human rights, conflict resolution or reconciliation or the promotion of religious or racial harmony or equality and diversity

- the advancement of environmental protection or improvement

- the relief of those in need, by reason of youth, age, ill-health, disability, financial hardship or other disadvantage

- the advancement of animal welfare

- the promotion of the efficiency of the armed forces of the Crown or of the police, fire and rescue services or ambulance services

- other purposes currently recognized as charitable and any new charitable purposes which are similar to another charitable purpose.

A charity must also provide a public benefit.[43]

Before the Charities Act 2006, which introduced the definition now contained in the 2011 Act, the definition of charity arose from a list of charitable purposes in the Charitable Uses Act 1601 (also known as the Statute of Elizabeth), which had been interpreted and expanded into a considerable body of case law. In Commissioners for Special Purposes of Income Tax v. Pemsel (1891), Lord McNaughten identified four categories of charity which could be extracted from the Charitable Uses Act and which were the accepted definition of charity prior to the Charities Act 2006:

- the relief of poverty,

- the advancement of education,

- the advancement of religion, and

- other purposes considered beneficial to the community.

Charities in England and Wales—such as Age UK, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB)[44] and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)[45] – must comply with the 2011 Act regulating matters such as charity reports and accounts and fundraising.

Structures

[edit]

As of 2011[update], there are several types of legal structures for a charity in England and Wales:

- Unincorporated association

- Trust

- Company limited by guarantee

- Another incorporation, such as by royal charter

- Charitable incorporated organization

The unincorporated association is the most common form of organization within the voluntary sector in England and Wales.[46] This is essentially a contractual arrangement between individuals who have agreed to come together to form an organization for a particular purpose. An unincorporated association will normally have a constitution or set of rules as its governing document, which will deal with matters such as the appointment of office bearers and the rules governing membership. The organization is not, however, a separate legal entity, so it cannot initiate legal action, borrow money, or enter into contracts in its own name. Its officers can be personally liable if the charity is sued or has debts.[47]

A trust is essentially a relationship among three parties: the donor of some assets, the trustees who hold the assets, and the beneficiaries (those eligible to benefit from the charity). When the trust has charitable purposes and is a charity, the trust is known as a charitable trust. The governing document is the trust deed or declaration of trust, which comes into operation once signed by all the trustees. The main disadvantage of a trust is that, like an unincorporated association, it lacks a separate legal entity, and the trustees must themselves own property and enter into contracts. The trustees are also liable if the charity is sued or incurs liability.

A company limited by guarantee is a private limited company where members' liability is limited. A guarantee company does not have a share capital, but instead has members who are guarantors rather than shareholders. If the company is wound up, the members agree to pay a nominal sum, which can be as little as £1. A company limited by guarantee is a useful structure for a charity where trustees need limited liability protection. Moreover, the charity has legal personality and can enter into contracts, such as employment contracts, in its own name.[48]

A small number of charities are incorporated by royal charter, a document that creates a corporation with legal personality (or, in some cases, transforms a charity incorporated as a company into a charity incorporated by royal charter). The charter must be approved by the Privy Council before receiving royal assent. While the nature of the charity will vary depending on the clauses enacted, a royal charter generally offers a charity the same limited liability as a company and the ability to enter into contracts.

The Charities Act 2006 introduced a new legal form of incorporation designed specifically for charities—the charitable incorporated organization (CIO)—with powers similar to a company but without the need to register as a company. Becoming a CIO was only made possible in 2013, with staggered introduction dates, with the charities with the highest turnover eligible first.

The term foundation is not commonly used in England and Wales. Occasionally, a charity will use the word as part of its name (e.g., British Heart Foundation), but this has no legal significance and provides no information about the charity's work or legal structure. The organization's structure will fall into one of the types described above.

Registration

[edit]

Charitable organizations with an income of over £5,000 and subject to the law of England and Wales must register with the Charity Commission for England and Wales, unless they are an "exempt" or "excepted" charity.[49][50] For companies, the law of England and Wales will usually apply if the company itself is registered in England and Wales. In other cases, if the governing document doesn't specify, the law that applies will be the one most connected with the organization.[51]

When an organization's income doesn't exceed £5,000, it can't register as a charity with the Charity Commission for England and Wales, unless registered as a Charitable Incorporated Organisation, in which case there is no minimum annual income.[52] With the increase in the mandatory registration level to £5,000 by The Charities Act 2006, smaller charities can rely on HMRC recognition to demonstrate their charitable purpose and confirm their not-for-profit principles.[53]

Churches with an annual income of less than £100,000 need not register.[54]

Some charities, referred to as exempt charities, aren't required to register with the Charity Commission and aren't subject to its supervisory powers. These charities include most universities and national museums, as well as some other educational institutions. Other charities are excepted from the need to register but are still subject to the supervision of the Charity Commission. The regulations on excepted charities were changed by the Charities Act 2006. Many excepted charities are religious charities.[55]

Northern Ireland

[edit]

The Charity Commission for Northern Ireland was established in 2009[56] and has received the names and details of over 7,000 organizations in Northern Ireland that have previously been granted charitable status for tax purposes (the "deemed list"). Compulsory registration of organizations from the deemed list began in December 2013, and it is expected to take three to four years to complete.[57] The new Register of Charities is publicly available on the CCNI website and contains the details of those organizations that have so far been confirmed by the commission to exist for charitable purposes and the public benefit. The Commission estimates that between 5,000 and 11,500 charitable organizations need to be formally registered in total.[58]

Scotland

[edit]

The approximately 24,000 charities in Scotland are registered with the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR), which also maintains a register of charities online.

United States

[edit]

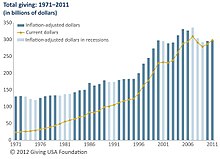

Total giving USA: 1979–2011

Total giving USA: 1979–2011

In the United States, a charitable organization is an organization operated for purposes that are beneficial to the public interest.[59] There are different types of charitable organizations. Every U.S. and foreign charity that qualifies as tax-exempt under Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) is considered a "private foundation" unless it demonstrates to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) that it falls into another category. Generally, any organization that is not a private foundation (i.e., it qualifies as something else) is usually a public charity as described in Section 509(a) of the IRC.[60]

In addition, a private foundation usually derives its principal funding from an individual, family, corporation, or some other single source, and it is more often than not a grantmaker that does not solicit funds from the public. In contrast, a foundation or public charity generally receives grants from individuals, government, and private foundations. While some public charities engage in grantmaking activities, most conduct direct service or other tax-exempt activities. Foundations that are generally grantmakers (i.e., they use their endowment to make grants to other organizations, which in turn carry out the goals of the foundation indirectly) are usually called "grantmaker" or "non-operating" foundations.[citation needed]

The requirements and procedures for forming charitable organizations vary from state to state, as do the registration and filing requirements for charitable organizations that conduct charitable activities, solicit charitable contributions, or hire professional fundraisers.[61][62] In practice, the detailed definition of a "charitable organization" is determined by the requirements of state law where the charitable organization operates, and the requirements for federal tax relief by the IRS.

Resources exist to provide information, including rankings, of US charities.[63]

Federal tax relief

[edit]

Federal tax law provides tax benefits to nonprofit organizations recognized as exempt from federal income tax under section 501(c)(3) of the IRC. The benefits of 501(c)(3) status include exemption from federal income tax as well as eligibility to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions. In 2017, there were a total of $281.86 billion in tax-deductible donations by individuals.[64]

To qualify for 501(c)(3) status, most organizations must apply to the IRS for such status.[65]

Several requirements must be met for a charitable organization to obtain 501(c)(3) status. These include the organization being organized as a corporation, trust, or unincorporated association. The organization's organizing document (such as the articles of incorporation, trust documents, or articles of association) must limit its purposes to being charitable and permanently dedicate its assets to charitable purposes. The organization must refrain from undertaking a number of other activities, such as participating in the political campaigns of candidates for local, state, or federal office. Additionally, the organization must ensure that its earnings do not benefit any individual.[59] Most tax-exempt organizations are required to file annual financial reports (IRS Form 990) at the state and federal level. A tax-exempt organization's Form 990 and some other forms are required to be made available for public scrutiny.

The types of charitable organizations that the IRS considers to be organized for the public benefit include those organized for:

- Relief of the poor, the distressed, or the underprivileged

- Advancement of religion

- Advancement of education or science

- Construction or maintenance of public buildings, monuments, or works

- Lessening the burdens of government

- Lessening neighborhood tensions

- Elimination of prejudice and discrimination

- Defense of human and civil rights secured by law

- Combating community deterioration and juvenile delinquency.[59]

A number of other organizations may also qualify for exempt status, including those organized for religious, scientific, literary, and educational purposes, as well as those for testing for public safety and for fostering national or international amateur sports competition, and for the prevention of cruelty to children or animals.

Criticism

[edit]

The charity has received various criticisms, for example:

- Charities sometimes give aid conditionally,[66] through eligibility requirements such as sobriety, piety, curfews, participation in job training or parenting courses, cooperation with the police, or identifying the paternity of children, charity models enforce the concept that only those who can prove their moral worth deserve help, motivating citizens to accept exploitative wages or conditions to avoid being subject to the charitable system.[citation needed]

- Charity is increasingly privatized and contracted out to the massive nonprofit sector, where organizations compete for grants to address social problems. Donors can protect their money from taxation by storing it in foundations that fund their pet projects, most of which have nothing to do with poor people.[67]

Economist Robert Reich criticized the practice of billionaires giving some of their money to charity, calling it mostly "self-serving rubbish".[further explanation needed][68] Mathew Snow of American socialist magazine Jacobin criticized charity for "creating an individualized 'culture of giving'" instead of "challenging capitalism's institutionalized taking."[69]

Charity fraud

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Charity fraud.[edit]

Charity fraud, also known as a donation scam, is the act of using deception to obtain money from people who believe they are donating to a charity. Often, individuals or groups will present false information claiming to be a charity or associated with one, and then ask potential donors for contributions to this non-existent charity. Charity fraud encompasses not only fictitious charities but also deceptive business practices. These deceitful acts by businesses may involve accepting donations without using the funds for their intended purposes or soliciting funds under false pretenses of need.

Charity regulators

[edit]

- Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Charity Commission for England and Wales

- Charity Commission for Northern Ireland

- Inland Revenue Department (Hong Kong)

- Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator

- United States Internal Revenue Service

See also

[edit]

- Aid agency

- Benefit corporation

- Charitable trust

- Charity watchdog

- Community organization

- Community organizing

- Cy-près doctrine

- Foundation

- Fundraising

- Grants

- Nonprofit organization

- Service club

- Governance

- Social enterprise

- Mutual aid, alternative to charity

- World Giving Index

- List of charities accused of ties to terrorism

References

[edit]

- ^ a b c

Reiling, Herman T. (1958). "Federal Taxation: What Is a Charitable Organization?". American Bar Association Journal. 44 (6): 525–598. JSTOR 25720402.

- ^ "Exemption Requirements – 501(c)(3) Organizations". Internal Revenue Service. 28 November 2018.

- ^ "UFF – Official Site". Archived from the original on 2021-08-19. Retrieved 2021-08-19.

- ^ Tilcsik, A.; Marquis, C. (2013). "Punctuated Generosity: How Mega-events and Natural Disasters Affect Corporate Philanthropy in U.S. Communities". Administrative Science Quarterly. 58 (1): 111–148. doi:10.1177/0001839213475800. S2CID 18481039. SSRN 2028982.

- ^ Jonathan Garton (2013), Public Benefit in Charity Law, OUP Oxford.

- ^ Note, for example, Acts 2:44–45: "And all that believed were together, and had all things in common; And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need." ZakÄÂt (charity) ranks as one of the Five Pillars of Islam.

- ^ "The Almshouse Association: A Historical Summary". Archived from the original on 2013-08-25. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ^ "Associational Charities".

Through the middle decades of the eighteenth century, a slew of new-style charities were created. They were directed at specific social problems (foundling children, prostitutes, venereal disease), funded by subscription, dependent on public support, and organized as associations of the living.

- ^ "Thomas Coram (1688–1751)". Archived from the original on 2016-12-25. Retrieved 2013-10-09.

- ^ "Captain Coram and the Foundling Hospital".

The result was the first children's charity in the country and one that 'set the pattern for incorporated associational charities' in general (McClure 248).

- ^ N. A. M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2004), 313.

- ^ Luddy, Maria (1988-01-01). "Women and charitable organizations in the nineteenth century Ireland". Women's Studies International Forum. 11 (4): 301–305. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(88)90068-4. ISSN 0277-5395.

- ^ T. R. Malthus (28 August 1992). Malthus: 'An Essay on the Principle of Population'. Cambridge University Press. p. x. ISBN 978-0-521-42972-6. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Tarn, J.N. (1973) Five Percent Philanthropy. London: CUP

- ^ "st george-in-the-east – St George-in-the-East PCC – Charity Number 1133761". stgeorgeintheeast.withtank.com. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ Van Slyck, Abigail A. (1991). "'The Utmost Amount of Effectiv [sic] Accommodation': Andrew Carnegie and the Reform of the American Library". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 50 (4): 359–383. doi:10.2307/990662. JSTOR 990662.

- ^ "Andrew Carnegie". Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy. Retrieved 2019-04-10.

- ^ "Andrew Carnegie, Philanthropist". www.americaslibrary.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ "Charles Booth (1840–1916) – a biography (Charles Booth Online Archive)". lse.ac.uk.

- ^ "Rediscovering Charity: Defining Our Role with the State".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Extension of Charitable Purpose Bill 2004 (Bills Digest, no. 164, 2003–04)" (PDF). Australia: Department of Parliamentary Services. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-29. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Charities". Queensland Government – Office of Fair Trading. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ^ "Fairfax Syndication Photo Print Sales and Content Licensing". licensing-publishing.nine.com.au. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ "Is your organisation a public benevolent institution?". Australian Taxation Office. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Charity subtypes". Australian Charities and Not-For-Profits Commission. 28 March 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Charities and Giving". Canada Revenue Agency. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ^ "Registered Charity". Canada Revenue Agency. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "1997. évi CLVI. törvény a közhasznú szervezetekrÅ‘l1".

- ^ Birds to holy rivers: A list of everything India considers "legal persons", Quartz (publication), September 2019. Archived 2019-11-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Charities Act 2009 (Act of the Oireachtas 6, section 13). Oireachtas Éireann (Parliament of Ireland). 2009.

- ^ Charities Act 2009 (Establishment Day) Order 2014 (Statutory Instrument 456). Minister for Justice and Equality. 2014.

- ^ "Charities and other Approved Bodies in Ireland under the Taxes Consolidation Act". Revenue Ireland. May 8, 2012. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012.

- ^ "Registration of Incorporated Trustees in Nigeria". Corporate Affairs Commission, Nigeria. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Guidelines-On-The-Tax-Exemption-Status-Of (2)".

- ^ "Charities Act". Singapore Statutes Online. 31 October 2007.

- ^ "Ministry of Culture, Community and Youth". Retrieved 25 July 2015.

- ^ Thor, Anatoliy. "Legislation on charitable organization in Ukraine".

- ^ "Understanding charity status and registration". National Council for Voluntary Organisations. Registering with the Charity Commission. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ^ "Background to the Charities Act 2006". House of Commons. Retrieved 18 February 2017.

- ^ Sparrow, Andrew (19 July 2012). "Labour could strip private schools of charitable status, says Stephen Twigg". The Guardian.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona; Asthana, Anushka (2017-06-06). "'Chilling' Lobbying Act stifles democracy, charities tell party chiefs". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ "Charities Act 2011". legislation.gov.uk.

- ^ "Charity Commission: Charities and Public Benefit". Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ^ "The RSPB Wildlife Charity: Nature Reserves & Wildlife Conservation". The RSPB. Retrieved 2020-01-31.

- ^ "Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals – RSPCA". RSPCA.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 July 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ^ "Seniors Network – Unincorporated Association". Archived from the original on April 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ "NCVO – Legal structures for voluntary organizations". Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ "Guarantee Company – Not for Profit Companies – Charities". Archived from the original on September 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ "Exempt charities (CC23)". www.gov.uk. 1 September 2013.

- ^ "Excepted charities". www.gov.uk. 11 June 2014.

- ^ "How to set up a charity (CC21a)". GOV.UK. 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Charity registration". gov.uk.

- ^ "Charities and tax". hmrc.gov.uk.

- ^ "Nonprofit Law in England & Wales". Council on Foundations. 2013-11-24. Retrieved 2020-07-21.

- ^ "Charity Act 2006". Archived from the original on 2007-05-22. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ^ "Our status". The Charity Commission for Northern Ireland. 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ "The Deemed List". Charity Commission for Northern Ireland. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- ^ "Registration list and expression of intent form". www.charitycommissionni.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2017-07-28. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ a b c "Publication 557: Tax-Exempt Status for Your Organization Archived 2020-05-11 at the Wayback Machine". Internal Revenue Service. January 2018. p. 27.

- ^ FoundationCenter.org, What is the difference between a private foundation and a public charity? Archived 2009-08-31 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2009-06-20

- ^ "NASCO National Association of State Charity Officials". Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "U.S. List of Charitable Solicitation Authorities by State". Archived from the original on January 27, 2014. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ^ Adriene Hill, "The worst charities: Get information before you make a donation Archived 2020-07-13 at the Wayback Machine", Marketplace, NPR, June 14, 2013

- ^ "The Ultimate List Of Charitable Giving Statistics For 2018".

- ^ "Applying for 501(c)(3) Tax-Exempt Status: Publication P4220" (PDF). IRS. March 2018.

- ^ "Arguments against charity". BBC. 2014. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

- ^ Spade, Dean (2020). "Solidarity not Charity" (PDF). Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ Reich, Robert (2020-04-12). "America's billionaires are giving to charity – but much of it is self-serving rubbish". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ Snow, Mathew (2015-08-25). "Against Charity". Jacobin. Retrieved 2022-03-25.

External links

[edit]

Media related to Charitable organizations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charitable organizations at Wikimedia Commons- "Charities" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. V (9th ed.). 1878. pp. 401–402.

Charitable giving and practices

| |

| Main topics |

- Alms

- Altruism

- Charity (practice)

- Compassion

- Donation

- Empathy

- Fundraising

- Humanity (virtue)

- Philanthropy

- Volunteering

|

Types of charitable

organizations |

- Charitable trust / Registered charity

- Foundation

- Crowdfunding

- Mutual-benefit nonprofit corporation

- Non-governmental organization

- Nonprofit organization

- Public-benefit nonprofit corporation

- Service club

- Social enterprise

- Religious corporation

- Voluntary association

|

| Charity and religion |

- Charity (Christian virtue)

- DÄÂna

- Tithe

- Tzedakah

- Sadaqah

- Zakat

|

| Charity evaluation |

- Aid effectiveness

- Animal Charity Evaluators

- Candid

- Charity assessment

- Charity Navigator

- CharityWatch

- Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis

- GiveWell

- Giving Multiplier

- Giving What We Can

- GreatNonprofits

|

| Further topics |

- Alternative giving

- Benefit concert

- Caffè sospeso

- Charity fraud

- Charity / thrift / op shop

- Click-to-donate site

- Drive

- Donor-advised fund

- Donor intent

- Earning to give

- Effective altruism

- Ethics of philanthropy

- List of charitable foundations

- Master of Nonprofit Organizations

- Matching funds

- Telethon

- Visiting the sick

- Voluntary sector

- Volunteer grant

- Wall of kindness

- Warm-glow giving

|

Authority control databases  |

| National |

- Germany

- United States

- Latvia

- Israel

|

| Other |

|